By Tom Zeller Jr. 11/04/2011 07:11am EDT | Updated December 6, 2017

At the end of September, the mayor of tiny Atkinson, Neb., sat calmly waiting for an invasion. David Frederick’s rural outpost of about 1,000 residents, set along the northeastern edge of Nebraska’s Sandhills, was about to see its population briefly swelled by a phalanx of U.S. State Department officials, itinerant union laborers, ranchers, farmers, environmentalists and reporters.

The crowds were headed Frederick’s way for a final public airing of opinions along the proposed route of the Keystone XL, a 1,700-mile stretch of pipe and pumps that would link a mammoth oil patch in Alberta to refineries on the Texas Gulf Coast. Nebraska would account for 257 of those miles, and maps show the proposed pipeline slicing clear through the state’s midsection, passing a few miles west of Atkinson.

But there are also lots of other towns near the proposed oil route, and it wasn’t clear even to Frederick how Atkinson’s high school gymnasium had been chosen for the national spotlight. “I’ve never been directly contacted,” the mayor said in his tidy Main Street office just hours before the throngs arrived. “This was very much presented as, ‘The State Department is having a party, you’re going to host it and you’re in charge of cleaning up afterward.’ “

Oil pipelines can have a similar way of just showing up, and as environmental groups or local residents dispute such landgrabs, acrimony tends to follow. Even for a pipeline, though, the debate surrounding the Keystone XL project has been rancorous. Charges of high-level malfeasance and corporate bullying mingle with accusations of environmental alarmism and energy ignorance in what arguably has become the most hotly debated stretch of oil pipeline in the nation’s history.

For more than three years, the State Department, which must grant a permit for the project to cross the U.S. border, has deliberated over the pipeline’s potential impacts and whether it is in the national interest. The rhetorical skirmishing has become increasingly heated during that time, with pipeline opponents accusing State of pandering to industry while supporters charge anti-oil activists with hijacking the issue to further their cause.

Much of the attention thus far has focused on the potential environmental impacts of the pipeline, as well as the State Department’s handling of the review. But a close examination of other aspects of the project suggests that the struggle is in many ways a symbolic one, pitting supporters of clean energy against those who say fossil fuels aren’t going away anytime soon. At the same time, the contributions of Keystone XL to employment and energy security in the United States often don’t match the claims of its proponents — and TransCanada, the company behind the project, is often guilty of fudging the numbers to make its case for the pipeline.

For his part, Mayor Frederick said he doesn’t mind the pipeline. He just wishes it went around, rather than through, the massive aquifer that feeds his community and hundreds of others across that part of the American breadbasket. He also said he wasn’t sure what his town stood to gain by having the line pass through the area. “I’m not sure how it would affect our local economy,” Frederick said. “But that’s how I’m going to be as a businessman and a local taxpayer. I want to know, what’s our benefit?”

NUMBER CRUNCHING

More than anything else, the raging debate over Keystone XL demonstrates the difficulty of generating answers universally accepted as “correct.” Oil interests, for example, concede that harvesting oil from the tar sands for eventual end-use in vehicles weighs more heavily on the environment than the conventional oil-to-gasoline life cycle, but experts differ on the extent of the damage. Estimates of the increase in carbon footprint have ranged from 5 percent, a figure favored by industry, to more than 30 percent, according to an analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Given the varying figures, analysts can either reject or confirm the oft-repeated claim, first made by former Vice President Al Gore, that “gasoline made from the tar sands gives a Toyota Prius the same impact on climate as a Hummer using gasoline made from oil.”

Call Michael Levi a skeptic on that point. The director of the Program on Energy Security and Climate Change at the Council on Foreign Relations, Levi used 15 percent as his benchmark and, after applying a little arithmetic to the Hummer aphorism, declared it untrue. Using the 15 percent figure, a Hummer running on conventional oil is still 4.3 times more carbon intensive than a Prius using gas derived from tar sands oil.

“It’s just dead wrong,” Levi said. “I can’t believe that in over two years Gore hasn’t bothered to correct this.”

When asked about the critique, Gore spokeswoman Kalee Kreider passed on an explanation from the former vice president’s 2009 book “Our Choice,” which first presented the Hummer analogy. Using extraction and processing data from a 2008 National Energy Technology Laboratory report, Gore determined that the ratio of greenhouse gas emissions for tar sands compared to conventional oil was “roughly five-to-one.”

The Department of Energy, meanwhile, gives the Prius only a three-to-one advantage over the Hummer in fuel efficiency. “The greater CO2 emissions resulting from the extraction and processing of oil from tar sands,” Gore wrote, “overwhelm the fuel economy benefits of a Prius.”

Levi argued, however, that the fuel-efficiency benefits of a Prius apply not just to the emissions that arise during “extraction and processing” of oil, but to discharges from the tailpipe. “Compare two worlds,” he said. “In the first, we all drive Hummers and use normal oil; in the second, we all drive Priuses and use oil-sands crude. Which is worse for the climate? There is zero question as to the correct answer.”

Despite his support for the pipeline, Levi has similar contempt for the rhetoric of some Keystone XL advocates — including an argument advanced in a pro-pipeline form letter he recently received from the Institute for 21st Century Energy, a project of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the nation’s preeminent business lobby.

Among other things, the institute’s letter claimed the Keystone XL project would “immediately create 20,000 jobs along the pipeline route. Furthermore, economic impact studies show that 250,000 permanent jobs will be created over the long term.”

Those 250,000 jobs, Levi says, are based on economic modeling of Canadian oil production more generally, and they have only a limited connection to whether or not the Keystone XL pipeline is built. “But they don’t tell you that,” he said. Moreover, the estimate is likely too high by at least a factor of 10, Levi said, though pinning a precise number on the impact is difficult given the opaque nature of the study that it’s based on.

“I don’t see any reason to block the Keystone XL pipeline, so long as local concerns in Nebraska are fairly addressed, something that shouldn’t pose a high hurdle,” Levi wrote in a blog post deconstructing the industry job projection last week. “The Keystone XL debate is a distraction from things that really matter to the future of U.S. energy and climate policy.”

“So long as the debate is front and center, though,” he added, “correct facts would be nice.”

JOBS, JOBS, JOBS

A fixation on job estimates has become an integral part of pushing the Keystone XL project — particularly by TransCanada and oil industry representatives, as well as among the project’s mostly Republican backers in the House, who have aggressively lobbied the State Department to expedite approval of a permit.

“This pipeline project is about increasing our energy security and putting America back to work,” House Energy and Commerce Chairman Fred Upton (R-Mich.) said in August, after the State Department issued its final environmental review. Like its previous iterations, that review concluded that the risks of the pipeline were limited.

“Completion of the Keystone XL Pipeline extension,” Upton continued, “will bring over 1.4 million barrels of oil per day into U.S. markets and create more than 100,000 American jobs.”

That six-figure jobs estimate came directly from TransCanada, which sometimes cites “numerous studies” as its source in press statements. For all practical purposes, however, those independent studies are really just one study — commissioned by TransCanada and published in June 2010 by The Perryman Group, a Texas-based economic and financial consultancy headed up by M. Ray Perryman, an economist and former Baylor University professor.

Applying what he describes as a proprietary, “dynamic input-output” economic modeling system to the KXL project, Perryman concluded in no uncertain terms that the pipeline offers Americans substantial benefits. “In addition to the sizable economic stimulus generated by the construction and development of the pipeline, the more stable supply of oil will lead to other positive outcomes,” he stated at the outset of his 56-page report.

His final estimate: The pipeline would create “118,964 person-years of employment.” (Person-years is economics-speak for the equivalent of one person working for one year — an important distinction from “permanent jobs,” because construction jobs are by nature temporary.)

Perryman’s numbers quickly drew rebuttals, but few were as thorough as the one that came from Ian Goodman, a California-based consultant. A collaboration with researchers at the Cornell Labor Institute, his analysis concluded, among other things, that the $7 billion number used to describe the cost of the project was misleading, because it included expenditures on the Canadian side of the border that would not create American jobs. A substantial chunk of the $7 billion had also already been spent on, among other things, building a connection between Steele City, Neb., and Cushing, Okla., the Cornell team argued. And a sizable percentage of materials for the pipeline would be obtained from foreign markets, further driving down domestic expenditures.

By Goodman’s estimates, the actual starting point for calculating the economic impact of Keystone XL in the United States was somewhere between $3 billion and $4 billion.

The Cornell analysis also dinged Perryman for using his own proprietary model, making it difficult to know how he’d arrived at the fortuitous economic ripples described in his report — including tens of thousands of indirect jobs in retail, printing and publishing and other ancillary industries that he claimed would be spurred by the pipeline.

Goodman and the Cornell team concluded that Keystone XL, while certainly a job-creator, could not possibly generate nearly 120,000 total jobs. In conversations with The Huffington Post after the publication of the Cornell study, Goodman further refined his analysis, suggesting that, in fact, “the incremental stimulus to the U.S. economy from KXL being built may only be about $2.3 billion,” and have so small an impact on jobs as to be almost meaningless.

“The incremental job impacts from building KXL are, at best, round-off error for the states along the pipeline route,” Goodman said, “and especially for the broader regional and national economies.”

The direct construction and manufacturing jobs, Goodman concluded, would be temporary and transient, with pipeline builders being imported, for the most part, to camps along the planned route. The largest boon would accrue to Texas and Oklahoma, Goodman suggested, where skilled pipeline labor is already on hand, meaning that more remote outposts, like Mayor Frederick’s town of Atkinson, Neb., would likely see few permanent jobs created.

Goodman is working with Cornell on an updated analysis.

Perryman disputes these findings, arguing, for starters, that the Cushing extension was included in his analysis because at the time it had not yet been completed, and more broadly, because it was important to understanding the project’s overall value to the United States.

“Excluding it from our prior analysis would have been inappropriate,” Perryman said.

In an email, Perryman also said that “virtually all major models are proprietary” and that they should be, given the decades invested in developing ones like his. He also said that his analysis only considered the U.S. portion of the Keystone XL budget, and that it had factored out the materials that would be procured outside the United States, bringing his starting point to a bit less than $5 billion in domestic expenditures.

Of course, in a down economy, any job is difficult to dismiss — and Keystone XL enjoys strong support among labor unions likely to benefit. And Perryman suggested the intense scrutiny of his report is a bit like counting angels on the head of a pin. “Like all models, it is not perfect. Every project is different, productivity can evolve ahead of the data [and] typical purchasing patterns might not be followed,” he said. “You can’t plan a project of this nature to the penny in advance.”

Such caveats, of course, have not stopped TransCanada from describing the pipeline as a $7 billion stimulus to the U.S. economy — nor from issuing ever-larger jobs estimates that go well beyond Perryman’s.

“Within days of receiving regulatory approval,” the company reported in a press release attending a visit to Washington last month by TransCanada’s chief executive, Russ Girling, “Keystone XL would create 20,000 construction and manufacturing jobs in the U.S during the construction phase. This includes welders, pipe-fitters, heavy equipment operators, engineers and many other trades. Investing billions in the economy would also lead to the creation of 118,000 spin-off jobs as local businesses benefit from workers staying in hotels, eating in restaurants and TransCanada buying equipment and supplies.”

By that tally, Keystone XL would represent nearly 140,000 jobs, and this accounting was repeated in public statements made by TransCanada on at least three other occasions recently.

When asked to clarify, TransCanada spokesman Shawn Howard initially said the company’s tally was sound. “The 118,000 is indirect/spin-off jobs as per Perryman,” Howard said in an email. The remaining jobs, he said, arise from 13,000 construction hires and 7,000 manufacturing jobs. Later, he corrected this, saying that the 118,000 number represented both direct and indirect jobs, as per Perryman. “That includes the 20,000 jobs during the construction and manufacturing stages of KXL,” Howard said.

The correction was lost on the National Association of Manufacturers, which parroted the erroneous higher numbers last Wednesday in an appeal to the State Department to approve the project.

TransCanada’s pipeline president, Alex Pourbaix, rankled at the notion that his company might be goosing the jobs numbers. “Let me just say, the suggestion that we’re going to build a $7 billion pipeline over 1,700 miles, broken up into 17 construction segments and 30 pump stations and we’re not going to create significant amounts of jobs, is one of the more ridiculous statements that I’ve ever heard,” he said.

But Goodman and the Cornell team are not the only ones questioning TransCanada’s math.

CFR’s Levi pointed the higher extrapolation — 250,000 jobs — that is now being used by industry advocates, as well as by TransCanada itself. That number also appears to come from Perryman, who describes it as the number of potential jobs — or technically, “person-years of employment” — arising from the “permanent increase in stable oil supplies associated with the implementation of the Keystone XL pipeline.”

Levi challenged that assertion on his blog last week, finding that it was likely 10 times too high — though he said precise accounting was all but impossible.

“I’m not claiming that Keystone XL will create 7,000 or 8,000 or 40,000 jobs. I find the entire approach of the Perryman study suspicious,” he wrote. “What I’m saying is that even if you buy its overall methodology, fixing the basic numbers leads you to much lower jobs estimates.”

FEELING SECURE

TransCanada and its supporters in the U.S. have long argued that the benefits of Keystone XL are all but apparent.

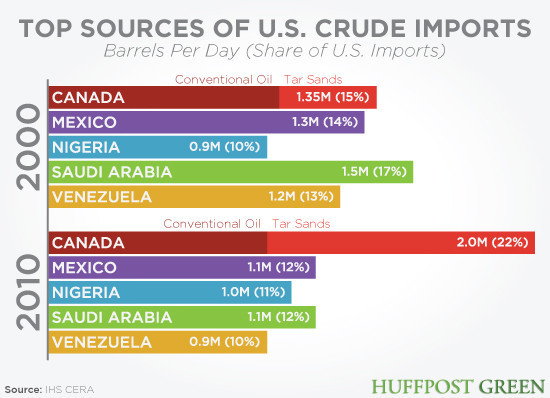

The United States imported roughly 2 million barrels of oil every day — both conventional and heavy stuff from the oil sands — from Canada in 2010, which represents about 22 percent of total imports, according to industry statistics. Building the pipeline would add capacity for as much as 700,000 daily barrels of crude oil to the 600,000 barrels carried on existing legs of the Keystone network. And all of it, supporters say, would be coming from a friendly, secure source north of the border.

It would also feed a hungry and expanding fleet of refiners on the Gulf Coast whose facilities are designed to handle the heavy sort of crude that would flow from Canada’s tar sands. Traditionally, those refiners have received their supply of heavy crude — some 2.9 million barrels per day — from Mexico and Venezuela, and to a lesser extent from Saudi Arabia and Nigeria. But Mexico’s oil resources have been in steady decline, and Venezuela has been pulling back on its deliveries as it eyes other markets for its crude — principally China.

If that slackening in supply isn’t replaced with product from Canada, pipeline backers say, refiners in the Gulf will get it one way or another — most likely by upping imported waterborne supplies from the Mideast or Nigeria.

“You have this huge refining center in the U.S. facing a decline of their existing supply, and then you have, about 1,500 miles north of there in Alberta, the second largest reserves of crude oil in the world in the Alberta oil sands,” said Pourbaix, TransCanada’s pipeline president. “That’s 175 billion barrels of recoverable reserves at today’s prices. And I think it just makes a lot of sense to connect that very, very significant supply source from a reliable and trusted ally of the U.S. … to the very significant refinery demand down in the U.S.”

Danielle Droitsch, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Counsel and director of the group’s Canada project, disputes many of the industry talking points, but she also said this sort of frank deconstruction of energy market push-and-pull is rarely presented to the American public. Rather, she says, they are fed a steady diet of rosy job projections and nebulous talk about energy security.

“The line that we keep hearing is that TransCanada is supposed to be some sort of Pied Piper, promising jobs and security to whoever will listen,” Droitsch said. “But make no mistake, the real motive is to boost the profits of international oil companies.”

“We know that this is not oil for the United States,” she added. “This is an export pipeline.”

An analysis released in August by the clean-energy advocacy group Oil Change International made this same case — pointing to a steady increase in the export of refined products out of the Gulf, and plans by customers for Keystone XL’s crude to continue the trend.

Whether this should be surprising or even controversial is an open question. TransCanada, the oil producers in Alberta and the shippers who have signed long-term contracts to use the pipeline — including large international outfits like Valero, Suncor Energy, ConocoPhillips, Marathon and Total — are not keen on Keystone XL because they want Americans to feel safe and employed. They want to make money. Right now, the Alberta oil patch is, for the most part, completely landlocked, and everyone in the tar sands food chain would like nothing more than to have a conduit to the global oil market.

Jackie Forrest, the Calgary-based director of oil sands analysis for IHS CERA, a global energy market research firm, noted that exports of refined oil products — chiefly diesel fuel — have long been a part of the Gulf Coast’s business, albeit a very small one. The vast majority of refined products arising from tar sands oil, she said, would be consumed in the United States — though she did say that exports are increasing, given a rising thirst for diesel fuel in Europe and Latin America.

“This demand has been a business opportunity for U.S. refiners, who can competitively supply these products and make more money from their underutilized refining assets,” Forrest said. “This dynamic has been happening for some time and has no relation to the Keystone XL decision. With or without the new pipeline, the U.S. will export refined products.”

That’s a variant on an argument frequently repeated by those inclined to approve the pipeline: block Keystone XL, and the dynamics of the market dictate that another pipeline proposal will sooner or later crop up to replace it.

“This probably doesn’t sound like a moral argument to environmentalists, but if we don’t buy it, it’s not going to sit in the ground,” said Charles Ebinger, the director of the Energy Security Initiative at the Brookings Institution. “TransCanada, or someone else, will probably ship it out elsewhere.”

Indeed, one natural question raised by the Keystone XL debate is why a pipeline isn’t simply run westward, to the Pacific Coast of British Columbia. Such a route would be less than half as long as Keystone XL’s journey to Texas.

The chief answer is that, for as long as it is, Keystone XL’s current route represents the path of least resistance.

Philip K. Verleger, Jr., a senior adviser to The Brattle Group and the president of PKVerleger LLC, a prominent energy market consultancy, pointed out in a recent analysis of the KXL that a westward pipeline out of Alberta would require agreements with dozens of Native American tribes occupying the corridor between the Canadian Rockies and the Pacific.

The western coast of Canada is also a dense patchwork of national and provincial parks and other protected lands that would make such a pipeline particularly difficult to permit, and Verleger said limitations on tanker activity in the area’s waterways leave the southbound route the only sensible one for Canadian oil interests. Building new refineries in Alberta, which could cost as much as $2 billion each, would also be prohibitively expensive.

Such realities have solidified Keystone XL’s backers’ resolute faith that the pipeline will be built, a view that is also driven by the insatiable thirst in economies new and old for oil.

U.S. oil demand is expected to dip only slightly over the next 20 years, from roughly 18.6 million barrels a day to 18.5 million barrels, according to IHS Cera, a consulting firm specializing in energy markets. Meanwhile, China is expected to nearly double its consumption during the same period to 17.5 million barrels a day. Globally, oil consumption is expected to rise from 86 million barrels a day to 110 million barrels by 2030.

Even accounting for the steady and continued uptake in the U.S. of electric cars and biofuels, IHS Cera’s Forrest said, weaning the American economy off oil will take multiple decades. “If you create a new pipeline that can take 700,000 barrels of crude from your closest neighbor, then that’s a good thing for energy security,” she said.

But clean-energy advocates and pipeline critics call those projections a fundamental failure of imagination. Energy security, they say, can only come by reducing demand for oil overall, through sound policy that encourages efficiency. Some studies have suggested that U.S. oil consumption could be cut by as much as 10 million barrels a day over the next 20 years, by increasing the fuel efficiency of cars, trucks and planes; improving building efficiency; and other measures.

Rejiggering how America imports its oil, Keystone XL critics also argue, is unlikely to provide much security. Oil is a global commodity, they note, and it responds to complex and often unpredictable global events — like, say, the recent turmoil in Libya.

“The impact of Keystone KL would be diluted over the whole world,” Levi said. “Sure, Canada won’t go the way of Libya. But when Libya goes way of Libya, it impacts the whole world.”

“There’s a difference between how much volatility there is, and how much you feel it,” he added.

Even a 2010 analysis commissioned by the Department of Energy, which noted that “a combination of increased Canadian crude imports and reduced U.S. product demand could essentially eliminate Middle East crude imports longer term,” also concluded that such an outcome would have little to do with the Keystone XL.

The global nature of the oil market makes it similarly difficult to answer one of the questions most pertinent to ordinary Americans: What will Keystone XL promise in terms of reduced gas prices? Verleger posited last spring that Keystone XL would drive up gas prices by 10 or 20 cents a gallon in the Midwest, where tars sands crude is currently bottlenecked.

TransCanada’s Pourbaix doesn’t deny the broader oil market mechanics, but noted that the price at the pump in the Midwest, or anywhere else, is a different matter altogether. His point was echoed by Jackie Forrest of IHS CERA, who noted that Midwestern drivers don’t currently enjoy any particular discount on gas, despite the over-supply of crude there. Her organization reckons that Keystone XL will nudge gas prices down, though in a June report, she and her co-authors also conceded that “many variables influence the price of oil.”

SKIRMISHES CONTINUE

The year-end deadline for a decision by the State Department may already be slipping amid continued turmoil, which includes recent moves by Nebraska’s governor to force a reconsideration of the route — something that Atkinson’s Mayor Frederick supports. “I’m sure the labor unions would build an excellent pipeline,” he said in a phone interview on Monday. “But that doesn’t affect the fact that we want it to go around our aquifer.”

Upping the ante on Monday, TransCanada suggested in a statement that Nebraska’s efforts might be unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, Senate Democrats raised the stakes last Wednesday when they requested that the State Department’s inspector general investigate the agency’s handling of the Keystone XL permit. Among their concerns: that TransCanada may have “improperly influenced” the selection of Cardno Entrix as the contractor for State’s environmental assessment.

Echoing a refrain from several environmental groups, the lawmakers also questioned whether email communications between State Department employees and TransCanada representatives, obtained by the environmental group Friends of the Earth, reveal a relationship that was too cozy or suggest a lack of objectivity — charges that the State Department has strenuously denied.

An assessment of State’s final environmental assessment by the Environmental Protection Agency is also looming. Another negative review could force the issue to the White House Council on Environmental Quality, which is responsible for helping to find consensus when agencies disagree.

Speaking last week, a senior State Department official told The Huffington Post that while the agency was still “on track” to complete its national interest review on the Keystone Pipeline by the end of the year, “the most important thing for us is to do the thorough review, make sure that we’ve covered all the bases, and that the decision is the best one for the country.”

Further delay would be unwelcome news for TransCanada, but even if officials were to give the project a pass, Nick Berning, a spokesman for Friends of the Earth, pointed to several potential state-level actions, including those now underway in Nebraska, as well as legal challenges.

“President Obama should reject this dirty and dangerous pipeline,” he said, “but that’s not the only way it can be stopped.”

Tom Zeller Jr., MIT Knight Science Journalism Fellow

SOURCE ARTICLE: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/keystone-xl-oil-pipeline-_n_1073840