By Zack Hale • 10 Nov, 2020

With razor-thin control of the U.S. Senate resting on the outcome of two special elections in January 2021, President-elect Joe Biden will likely be forced to pursue much of his energy and climate agenda through executive orders and administrative rulemakings.

And that may require the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to confront a tough decision: whether to issue a revamped Clean Power Plan-like rule for the U.S. power sector.

“Given the fact that Biden’s probably not going to have a compliant Senate to work with, don’t look for him getting policy done through a reconciliation bill, or even an ambitious climate bill,” Eric Washburn, a former senior advisor to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., said on a post-election webinar hosted by Bracewell LLP. “He’s going to have to do what he’s going to do to promote his clean energy and climate agenda administratively, and that’s going to put a lot of pressure on EPA. I suspect you’re going to see a new Clean Power Plan.”

The Trump administration replaced the Obama-era Clean Power Plan in June 2019 with its own scaled-back regulation, the Affordable Clean Energy, or ACE, rule. The Biden EPA is widely expected to ask the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to pause litigation over the rule before it can issue an opinion after hearing oral arguments last month. But that also raises the question of what an ACE rule replacement should look like.

Finalized in 2015, the Clean Power Plan adopted a systemwide approach designed to cut carbon emissions from fossil fuel-fired generators 32% below 2005 levels by 2030. However, in an unprecedented move, a skeptical U.S. Supreme Court in February 2016 voted 5-4 to stay the regulation before it had been reviewed by a federal appeals court and, therefore, it never took effect. Since then, the court’s conservative majority has grown to 6-3 with the recent addition of Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

In contrast to the Clean Power Plan, the ACE rule relies exclusively on efficiency upgrades called heat-rate improvements at existing coal-fired power plants. It is only projected to cut CO2 emissions less than 1% by 2030 beyond a business-as-usual approach relative to 2005 levels.

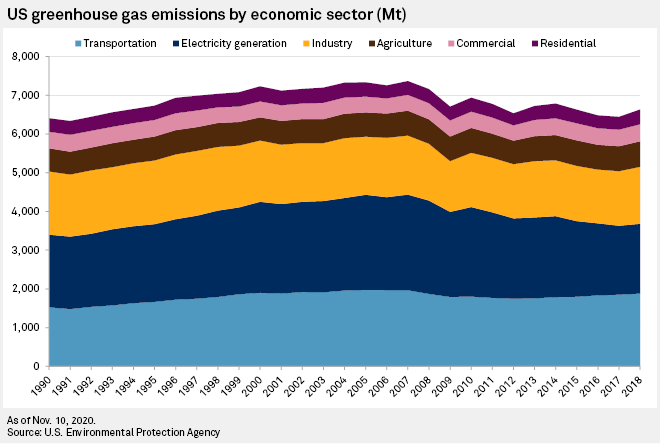

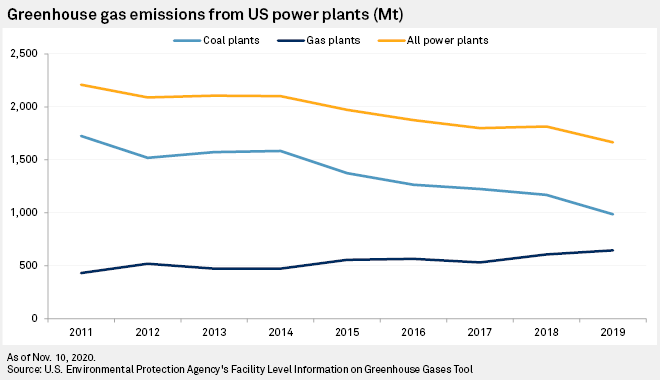

In public comments on the ACE rule, the Edison Electric Institute noted that the U.S. power sector will have complied with the final 2030 goals of the Clean Power Plan in terms of gross emissions reductions before the 2022 start date for the program. Nevertheless, electricity generation is still the second-largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions after transportation, according to EPA data.

‘Out of date’

“This is not a situation where just turning back the clock is going to be the most effective thing to do,” Janet McCabe, former assistant administrator of the EPA’s air office during the Barack Obama administration, said in an interview. “The Clean Power Plan is out of date now.”

As a member of the Environmental Protection Network, an advocacy group launched in January 2017, McCabe led a workgroup of former EPA staff in releasing detailed recommendations for how a future administration should address stationary sources of emissions. First among its recommendations is to recognize limited EPA resources by prioritizing early actions that can make real reductions in pollution.

Assessing the odds of a new Clean Power Plan, McCabe noted that Obama tried to secure bipartisan climate legislation in his first term only to see the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill die in the Senate.

“We’ve been down this road before, which was try legislation first and then turn to regulation, and I think that there’s no time to lose here, really,” McCabe said. ” I think it’s going to be hard to avoid wanting to look at whether there’s a regulatory approach for power plants under the Clean Air Act.”

Legal risk

While supporters of the Clean Power Plan have maintained its systemwide approach under Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act is legally defensible, critics point to the Supreme Court’s conservative tilt.

“Going back to the approach that the Obama administration took on the Clean Power Plan, I don’t know that they would actually try to do that because I think their chances of getting the Supreme Court to uphold that rule are pretty low,” Jeff Holmstead, former head of the EPA’s Office of Air and Regulation in the George W. Bush administration, said in a July interview.

A Biden administration would be wise to avoid pouring resources into a regulation that closely resembles the Clean Power Plan, said Nathan Richardson, an assistant law professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law and visiting fellow at the independent research organization Resources for the Future.

However, Richardson said he could also envision a Biden EPA pursuing a slimmed-down version of the Clean Power Plan that demands far more aggressive CO2 cuts from existing coal plants relative to the ACE rule, which did not set specific emission limits.

“That would be simpler, probably easier to put in place and have less legal risk than the kind of complicated power sector-wide approach that the Obama administration tried in the Clean Power Plan,” Richardson said.

Fine particulate matter standards

Another potentially underrated tool at the Biden EPA’s disposal could be the National Ambient Air Standards, or NAAQS, for fine particulate matter, or PM 2.5, Richardson said. Coal-fired generators are one of the nation’s largest sources of fine particulate matter and could be impacted by a move to strengthen the NAAQS for PM 2.5.

Against the advice of scientific experts, the Trump EPA proposed in April to retain the EPA’s current PM 2.5 standards. The EPA has signaled plans to finalize the rule after a draft version clears interagency review, a move the Biden EPA could reverse.

“I do think the chances of tightening down the NAAQS, especially the PM NAAQS, are a little bit underplayed in these discussions,” Richardson said.